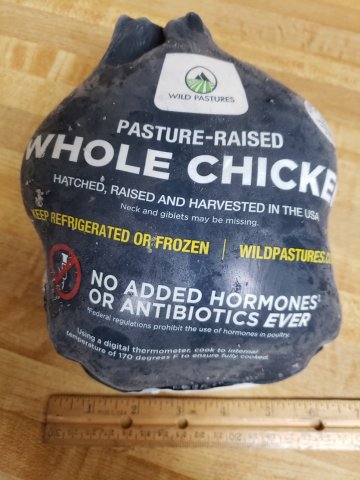

This Thanksgiving we did not have turkey. A guest provided a ham, so a turkey would have been 'way too much food. So I roasted a mini-turkey, aka a Wild Pastures whole chicken.

I have to say, it was really, really good. I'm more than ever convinced that mass-produced food is bred for lack of flavor. The day before, I had rubbed it all over, lightly with honey and fresh lemon juice, then heavily with a dry mixture of salt, black pepper, and "Alliums Plus," which is my homemade ground spice blend of various alliums, green peppercorns, and celery seed. I filled the (small) cavity with peeled and lightly smashed garlic cloves, a couple of large springs of rosemary, and half a lemon, and let it dry brine (uncovered) overnight in the refrigerator. The seasoning was light enough to let the chicken flavor shine.

Almost as good is what happened after the meal was over.

I've tried off and on for years to make my own broth/stock, with minimal success. Oh, I would succeed in creating broth, but it would turn out to be no better than I could get at the grocery store for a whole lot less work. But this time was different.

After our Thanksgiving meal, I dug out the crockpot and put in the chicken carcass (which fit perfectly) along with a collection of onion skins and leg and thigh bones from previous meals of Wild Pastures chicken parts, which I had collected in the freezer. I filled the pot with water and let it simmer until the following day. I added no seasoning additional to whatever came with the carcass (minus the half lemon, which I removed).

After removing all the solid material and straining the liquid, what to my wondering eyes should appear was a hearty, delicious stock. You can tell how much good came out of the bones by the way it jiggled when cooled.

Now I am again excited about making stock. It was a small batch, which helped, as did keeping it simple, but I'm looking forward to, rather than dreading, the next opportunity.

What do you picture when you hear autism called a "spectrum"?

I think of a linear scale, the kind you see in so many surveys, such as this:

That's the image that comes to my mind, but I don't believe it's accurate.

Recently, I saw a short video of a man who dusted a thin metal plate with sand, and then drew a violin bow along one side, the vibrations creating a pattern with the sand. By placing his fingers on different combinations of points on the edge, he could create beautiful, complex patterns. These are called Chladni figures, and you can find out more in this demonstration, which is under 10 minutes long.

This strikes me as a much more reasonable way of describing the set of people that we have decided to label "autistic."

What of other people? What of other dimensions?

Maybe the true value of diversity lies not in magnifying our differences but in celebrating our beautiful patterns?

Permalink | Read 130 times | Comments (0)

Category Health: [first] [previous] Random Musings: [first] [previous]

Permalink | Read 172 times | Comments (0)

Category Inspiration: [first] [previous]

Forevergreen is a new, short, animated film. I know nothing about it except that a friend recommended it, and I found it enjoyable and moving. I belive this preview (of the entire film) will only be available for free for a week, so if you're interested, watch it soon. It's 13 minutes long.

Permalink | Read 180 times | Comments (0)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] Conservationist Living: [first] [previous] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [newest]

I had an idyllic childhood. Not perfect, but as close to that as anyone I know. And one of the best parts, I now realize, was growing up with engineers.

Schenectady, New York, where I spent the first 15 years of my life, was the home of the General Electric Company. As it did the skyline, GE dominated our lives, night and day. My father was an engineer, as was his father, and his father's father, and he worked in GE's General Engineering Laboratory. My parents met there, where my mother, a mathematician, also worked. Many of our closest friends were engineers or employed in related fields. Schenectady in those days was a hotbed of science-and-engineering-types, and as far as I could tell, everyone I knew was smart. Smart was normal, and not just among the scientific folks. I suspect that living in Schenectady in its heyday resembled what I imagine living in Silicon Valley or the Seattle area is today.

I'm not talking about genius-level, though there were certainly some of those, but rather down-to-earth people with practical experience and skills, who also read a lot and loved to have discussions about ideas and on just about any subject.

Not that I appreciated it at the time as I should have; I took it for granted. But my recent "archivist" work with my father's journals and other writings has made me realize what a blessing it was to grow up in such a community. They even had their own way of speaking: their conversations were filled with jokes and wordplay, exaggerated and understated language, and what I realize now was an advanced everyday vocabulary. It wasn't until I had had much more experience outside of our parochial bubble that I realized that there are many people who find what I consider a normal vocabulary to be a sign of arrogance, who take the exaggerated/understated language literally, to the point of misunderstanding or even offense, and who either don't understand or don't appreciate the humor.

It takes all sorts and conditions of men to make a world, many of them wonderful. If you understood the "sorts and conditions of men" reference, you are part of a different distinct community, one I did not come to recognize and love until more than 30 years ago. Appreciating other cultures and especially loving one's own are not mutually exclusive conditions.

What chiefly concerns me is that we seem to have entered an age when differences are being replaced by diagnoses. The other day, a new friend was telling me about her son, who in high school was triply exceptional: He excelled in academics, in music, and in sports. It's not uncommon to see people who do very well in two of those areas, but three is a rarity. At one point, he was moved to express the concern that he might be "on the spectrum." What social pressures drive an obviously intelligent, capable, and well-rounded child to label himself with a diagnosis? Why do teachers and doctors (and even parents) put so much effort into finding boxes into which they can squeeze children?

As I told my friend, in my day, in my world, we used another term to describe being "on the spectrum."

We called it normal.

Permalink | Read 161 times | Comments (1)

Category Children & Family Issues: [first] [previous] [newest] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [newest] Everyday Life: [first] [previous] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous]

As I wrote in Let the Worms Decide, I decided to do my own experiment on what our composting worms think of junk food.

I began the experiment with the worms "hungry"; I had let the available food dwindle 'way down in hopes of increasing their willingness to accept my offerings. I placed a clean paper towel on top of the moisture mat for greater visibility for the camera; normally their food goes under the mat, but I knew the clever little creatures would find it. From left to right, top to bottom: chocolate chips (60% cacao), a Starburst candy, two gummy bears, two Hallowe'en-sized Twizzlers (strawberry), an Airheads candy, brown rice, a piece of paper towel soaked with local, raw honey, some arugula, and a banana skin.

Four days later, the chocolate chips had apparently begun to mold, and the Starburst was completely covered in it. The other candy had softened and faded, but was untouched. The rice was very popular, but it's hard to tell what they thought of the honey. The arugula showed a small amount of interest, and there was some activity at one end of the banana skin.

After seven days I took pity on the worms and ended the experiment so I could give them a larger quantity of food I know they like. As you can see, there was a lot more worm activity. The rice was completely gone, and there had obviously been a lot of action around the arugula and the end of the banana (note all the worm castings). The chocolate showed a reasonable amount of interest and there were a number of worms around the candy—but they may have been munching on the paper towel. The Airhead seems to have been totally ignored.

It's hard to draw any firm conclusions. The worms can't really eat many items until the bugs and microfauna have done their pre-processing work, and some foods may take longer than others. I don't know why the arugula went so slowly; usually greens go quickly, but perhaps arugula is too "spicy" for the worms—I know they don't like the strong-flavored lemon balm.

I would have thought that the candy, being mostly sugar, should have been easy for them to handle. But I was wrong. According to my Brave browser's AI,

Red wiggler worms should not eat candy. Candy is high in sugar and often contains oils, artificial ingredients, and other additives that can harm the worms or disrupt the balance of the composting environment. While red wigglers can consume a variety of organic matter, including fruits and vegetables, they should not be fed processed foods like candy, cookies, or cake, as these can lead to poor bin conditions and attract pests.

So there you go. Ultra-processed foods are bad for worms, and probably for people, too. Then again, chocolate is bad for dogs, they say, and good for people (in limited quantities), so make your own decisions.

Grace is getting an MRI, and ECG, and bloodwork (including thyroid) tomorrow morning at Dartmouth. I'm not sure how much the thyroid medicine is working, so we'll see what the numbers say. Her skin is very dry and she has rashes in places, and also the dryness is itchy so she scratches it, sometimes to bleeding.

Today is day +641! What a big number, and we are thankful. We're coming up on two years since diagnosis and oh, how far she's come!

Thank you all for caring about our little one big four-year-old!

Permalink | Read 220 times | Comments (2)

Category Pray for Grace: [first] [previous]

"Let the Worms Decide" is an Epoch Times article that caught my eye first because of the author, Joel Salatin, and secondly because I knew what kind of worms he was talking about. We've been vermicomposting since 2009, and I know a little bit about what our worms will and will not eat.

Salatin begins with a story from a middle school program he visited in California, where students worked on a small farm half a day each week.

They had a worm box about 8 feet by 3 feet by 3 feet. Imagine an oversized coffin. If you want to see children get excited, show them a worm box. It’s mesmerizing with all the slithering, slimy worm activity....

One week, the farmers assigned homework: “Bring food on Monday.” The students dutifully brought some food: Twizzlers, Gummy Bears, Froot Loops—you get the idea. They placed their “food” in one end of the worm box. The farm ladies put different items in the other end: an apple, a pork chop, and a glob of yogurt, among other things. The following week, the students, eager to see what had transpired, ran to the box and opened it.

They pulled out their Gummy Bears, Twizzlers, and Froot Loops—untouched. When they tried to find the food items that the farmers had placed at the other end, all that food was gone. The day’s lesson was obvious: “Why would you want to eat something worms won’t even eat?” I'll bet a lot of young people made some different eating decisions that day.

Tongue not totally in cheek, Salatin proposes turning our expensive—and too-easily corrupted—food safety testing over to composting worms.

I’ve known and worked with many worm farmers over the years who explain how sensitive their “livestock” is to unacceptable items placed in their boxes. If they like the substance, they devour it readily. If they don’t, they move away and give it a wide berth.

If worms are that decisive and timely to determine healthy versus unhealthy things in their environment, why not ask them to share their preferences with all of us?

Worms don’t vote, don’t listen to lobbyists, don’t invest in Wall Street, or watch ads. They are about as objective a researcher as you could ever want. Goodness, they aren’t even swayed by money.

Here’s my idea: why not get a small plot of land—perhaps 5 acres—and set up 100 worm boxes? Everything Americans apply to the soil or put in our mouths would undergo the worm test for a week. What the worms ate would get a green light. What the worms didn’t eat would get a red light.

We could hire a couple of college students to run the program. If glyphosate is really innocuous, let’s see if the worms like it. If Coca-Cola is really nutritious, let’s see if the worms like it. Pour it in and see if they want to come to that area, or if they avoid it like the plague. If Red Dye 29 is a wonderful food additive, or monosodium glutamate (MSG), put them in the worm bed and let the worms vote.

Based on my experience, I see a few problems with this scenario, as I'm sure Salatin himself does. Worms will eat (and detoxify) some really nasty things, given enough time for their cohabiting microorganisms to break them down. The farmers who sold us our system have huge vermiculture setups in which they say the worms will devour battery acid in small quantities. Just because you can convince a worm to eat something, that doesn't mean I want it in my food. But the one-week test would probably take care of that problem. Maybe the worms will eventually eat something, if they get hungry enough, but they definitely have their favorites and, like a small child at the dinner table, will go for the good stuff first.

That same small child may reject his beets despite their certified goodness, and my worms will reject things I find great. Like homegrown, organic lemon balm. Or citrus peels. (Granted, I never tried them on the chocolate-covered variety.) Some worms don't like broccoli; fortunately, ours eat it right up. So it's not a foolproof system.

That said, Salatin makes an important point: If something we're doing causes natural systems to thrive, that could be a clue that we may be going in the right direction. On the other hand, a failing system is a red warning light that should give us pause.

Stay tuned for the results of my own experiment. We have leftover Hallowe'en candy, including the above-mentioned Twizzlers. I plan to make an offering to the worms and see what they have to say.

Permalink | Read 209 times | Comments (1)

Category Education: [first] [previous] [newest] Health: [first] [previous] [newest] Politics: [first] [previous] [newest] Food: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Conservationist Living: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

After spotting this image on Facebook, I tracked it down to (I think) the creator: "Catturd" on X, made using Grok. The caption reads,

Just spotted on I-95 headed to Florida.

As a Floridian who is grieving for the people of New York City, even the ones who voted for Mamdani, and now more than ever worried for our friend the NYC detective, I can't pass this up.

I do, however, agree with the X poster who pointed out that it would have been a much shorter trip to go to the state that has been named the #1 freest state in America. (Florida was ranked #2.) Maybe Lady Liberty is also tired of cold weather.

Working my way through my father's vast collection of writings, I occasionally find a gem I wish to share.

(Okay, so "vast" is a relative adjective, and perhaps an exaggeration—it's not as if I'm working through the letters of C. S. Lewis or something—but in personal terms it's accurate.)

This came from Dad's 1987 journal documenting his Elderhostel experience at Ferrum College, in Ferrum, Virginia. The program is now called Road Scholar, and no longer has the age restriction, but at that time it was primarily for those over 65, that being the age at which most people retired and could go on such adventures.

Also at the college were a group of gifted 6th graders from nearby Martinsville. They also were at the ice cream social and were told by their teachers to mix with the old folks, so it turned out to be a pleasant evening. I think the future governor of Virginia may have been amongst them. One of the women asked the boy about what they were doing, and then said, "I'll bet you didn't expect to see so many old folks here."

He replied, "I don't know, I haven't seen any yet."

Smart and wise. I could envision voting for him.

Permalink | Read 250 times | Comments (0)

Category Travels: [first] [previous] Random Musings: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest] Glimpses of the Past: [first] [previous] [newest]

Ahhhhh. My mind and body are once again aligned with Nature.

It often pays to find the story behind the headline—or the social media post.

The Facebook blurb from our local library was annoying. Here's how it began:

1000 BOOKS BEFORE KINDERGARTEN: A round of applause for A----, who has read another 1,000 books before kindergarten—for the third time! On her way to becoming a young, brilliant scholar, Seminole County Public Libraries is proud to be part of A----’s journey as she grows her vocabulary, boosts her critical thinking, and enhances her cognitive development.

I was annoyed, but looked further and discovered that our library has a program to encourage parents to read aloud to their preschool children. It's a little sad that adults need stickers as an incentive to read to their children, but we've all been there with some good habit we're trying to acquire. So it looks like a good thing.

What bothered me about the Facebook post was the implication that the achievement belonged to the child, and that she had actually read 3000 books. I've known a few kids who taught themselves to read before formal schooling, but that's not what is meant here. Maybe I'm being pedantic, but I don't think so: As valuable as being read to is, it is not the same as actually reading the words on the page.

I have a similar problem with adults who claim to have read a book when actually what they've done is listen to someone else read it to them. Don't get me wrong; I enjoy audio books and find them invaluable for absorbing content while doing repetitive work, exercising, and driving. But that's a different experience from reading, even for adults, and especially for a child who hasn't yet developed the skill of decoding print.

And I'm not sure it's a good idea to let a child believe he has done something worthy of great praise when the effort was on the part of his parents. Sort of like getting an A on a homework assignment done 95% by your dad. Or getting a Pulitzer Prize for something written by ChatGPT.

Curious about the quantity of books, I looked up my own reading tally. I have been keeping track of the books I read since 2010 (making note of the few that were audiobooks). I consider myself an avid reader, but it took me until mid-2024 to reach the 1000-book mark. So I commend all the parents who achieved that in reading to their preschool children.

Then again, from what I can tell, my just-turned-two granddaughter is probably nearing the 750 mark with Sandra Boynton's Barnyard Dance, including many repetitions of turning the pages herself and telling the story as she remembers it, complete with stomps and claps.

And no, I don't include books read to grandchildren in my own reading list, even though I don't limit myself to adult-level reading.

It is usual to speak in a playfully apologetic tone about one's adult enjoyment of what are called "children’s books." I think the convention a silly one. No book is really worth reading at the age of ten which is not equally (and often far more) worth reading at the age of fifty—except, of course, books of information. The only imaginative works we ought to grow out of are those which it would have been better not to have read at all. — C. S. Lewis, On Stories

Although I don't agree completely with the practice, I'm more inclined to keep teens away from alcoholic beverages than from vegetable spiralizers. But here's a funny story about that.

A friend was at the grocery store, and decided she'd like a little wine with dinner. So she picked out a good one, and set the bottle in her cart. At check-out, she was asked to prove that she was older than 21. Now this friend looks quite young for her age, but she is older than I am, and I've seen more than seven decades. As the lady said in the spiralizer story, When did the world go completely mad? If the cashier can't tell at a glance that I'm not 20 years old, I don't want her counting my change. And if the store thinks she's incapable of such a determination, how is it they trust her to make any decisions at all?

I don't know why my friend didn't have her driver's license with her at the time, but she didn't, and reluctantly decided to forgo her dinnertime libation. But here's where the story gets interesting.

As many of us do in such situations, it wasn't until after she was done shopping that she thought of what she should have said. Because she was not alone in the store.

Hang on a second. My grandson will buy it for me.

Then again, she probably wouldn't have wanted to get him in trouble for buying alcohol for seniors.

Permalink | Read 359 times | Comments (2)

Category Just for Fun: [first] [previous]

On this 610th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt, it's time to reprise (again) Kenneth Branagh's version of Henry V's famous speech. (Shakespeare's version, that is.)

Permalink | Read 406 times | Comments (0)

Category Inspiration: [first] [previous] [next] [newest]

I publish this here because I know there are people with whom it will resonate, although it apparently runs contrary to the experience of the majority. Why else would they be so anxious to banish silence from our lives?

A prime example is our water aerobics classes at the local community therapeutic pool. The warm-water exercise is worth the struggle for me, but it is indeed a struggle, every time. For some reason the instructors believe that people exercise better when accompanied by loud music and a headache-inducing drum beat. We've managed to find the instructors who will at least keep the volume down to where I no longer have to wear earplugs, but the incessant noise and throbbing beat continue.

To my fellow classmates who may think I am rude, unfriendly, or merely unhappy, I don't mean to be any of the above. But please don't tell me to smile. It takes so much effort to fight the sensory assault that social politeness is often a casualty.

With one exception: All too rarely, we play games with small beach balls: bouncing, hitting, throwing, challenging just ourselves or in competition with others. It's not unkindly competitive—half the fun is figuring out how to include everyone of varying skill and physical ability levels—but it's exciting, and when we're doing that I manage to tune out the music almost completely. I have no idea why. It's the most active of the physical work we do in those classes, and yet it is the only time I feel relaxed and free.

Often I even smile.

.jpeg)